I’ve always wondered what my neurodivergent brain looks like after a marathon prompt-engineering session—fizzing like Pop Rocks (it’s a candy from the 90s) or just humming along? A recent MIT case study, “Your Brain on ChatGPT,” finally straps electrodes to that curiosity and gives us pictures. It’s a vast data set even with its demographic limitations (n=54 and n=18, writers at R1 institutions) that deserves our attention, but it measures just the product of writing instead of the process of metacognitive, iterative writing with large language models (LLMs) that our Kennesaw State University team developed and is testing (Rhetorical Prompting Method). Let’s unpack the findings, then talk about what the study leaves on the cutting-room floor.

Why This Study Matters

Design in a nutshell. 54 college participants wrote 20-minute SAT-style essays under three conditions: ChatGPT-4o only, Google Search only, or “brain-only” (no external tools).

What the EEG saw. Neural connectivity shrank as tool support grew; the brain-only group lit up the widest networks, Google search sat in the middle, and ChatGPT support produced “the weakest overall coupling” (p.135).

Behavioral echoes. ChatGPT writers “struggled to quote their own prose” minutes later and reported low ownership (p. 30).

Bottom-line warning. Findings indicated that convenience truncated critical evaluation; LLM use “diminished users’ inclination to critically evaluate the output” (142).

These are important signals for anyone teaching or researching AI-assisted writing. Lower engagement and fuzzy memory shouldn’t be hand-waved away. But I would posit to you that there is a middle ground, and KSU researchers have explored that area and continue to, both with first-year writers and with adult learners on Coursera, publishing initial results in The Conversation and in forthcoming academic papers.

The Product-Based Lens: Where the Study Falls Short

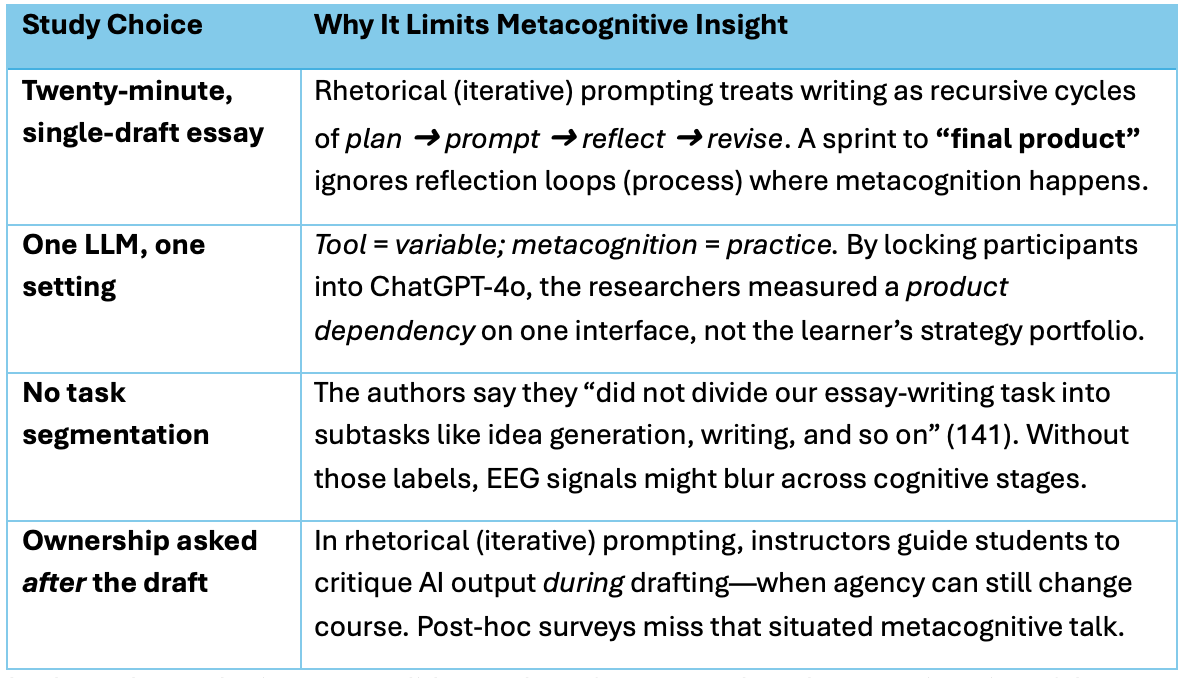

The study gives us a solid snapshot of outcomes, but almost no imaging of the thinking moves between prompt and prose. It’s like timing a chef’s plating speed but never tasting the food. Process-oriented writing - where students plan, draft, reflect, and revise - significantly amplifies metacognitive awareness compared to timed, document-centric writing. When writers pause to journal about their thought process, setbacks, and strategy choices during drafting, they engage in active self-monitoring and evaluation: a hallmark of metacognition. This sustained engagement enables writers to track not just what they write but how they think, identify cognitive barriers in real time, and adjust their approach, thereby improving self-regulation. In contrast, timed writing tasks typically emphasize content production under pressure, minimizing opportunities for reflective pauses and strategic planning. As a result, writers in process-based environments tend to develop deeper awareness of their thinking strategies and are better equipped to transfer insights to future writing assignments. Here’s a visual that helps me think about the study’s limitations.

Reframing “Cognitive Debt” with Iterative Prompting

The authors warn that repeated LLM use narrows idea space and erodes memory—a pattern they label “accumulation of cognitive debt” (140). I agree—if writers stay in one-and-done mode, what we call zero or single-shot prompting. In KSU’s Rhetorical Prompting Method, the iterative cycle does the opposite:1

Audience & purpose check before the first prompt.

Prompt, receive, reflect: ask why an answer feels off.

Re-prompt or edit to align with rhetorical goals.

Ethical Wheel step 4: “Did I edit the output for usefulness, relevance, accuracy, harmlessness?”

Those deliberate pauses tax - and therefore exercise - the very neural networks the EEG study sees dimming. Cognitive load isn’t the enemy; unexamined outsourcing is. The idea of cognitive load, when we think of digital writing, can also be a loaded phrase that really means “cognitive distribution” or shift in how writers deploy and manage their internal resources.

What Future Research Should Capture

The MIT team plans to add diverse participants, multiple LLMs, and finer-grained brain metrics, all of which will deepen and expand future findings (141). I’d add:

Prompt-interaction logs aligned with EEG timestamps to see which neural bursts map to which rhetorical decisions. No product-based writing.

Think-aloud protocols so we can hear metacognitive talk, not just infer it.

Longitudinal design asking does iterative prompting restore those alpha-beta connections once learners internalize reflection habits?

Hybrid conditions where AI handles mundane phrasing while humans steer argument structure, testing my “human at the helm” mantra.

5. Takeaways for Educators & Writers

Show the wiring diagram. Share studies like this with students so they see the neural stakes of copy-paste complacency. The article has some amazing visuals.

Grade the journey, not just the draft. Encourage prompt logs and reflection notes; reward strategic engagement over polished first drafts.

Lean on AI as a sparring partner, not a ghostwriter. Let the machine propose, but make the human dispose - and disclose.

Closing Thoughts

Yes, the MIT team has captured an eye-opening brainprint of LLM convenience. But until research instruments follow the process of iterative prompting, we’re still measuring footprints instead of the walk. When writers engage in recursive, reflective prompting, those dimmed neural circuits will light back up, like today in Atlanta, thunderstorms included.

Works Cited

Kosmyna, Nataliya, et al. Your Brain on ChatGPT: Accumulation of Cognitive Debt When Using an AI Assistant for Essay Writing Task. MIT Media Lab, June 2025, PDF, pp. 1–206.

Please steal this work! The Rhetorical Prompting Method and its associated content are licensed CC:BY and are open/free to anyone who wants to use them. #OpenPedagogy